Where The Wild Things Are

Constructing destructive tar sands oil pipelines through First Nations' lands is the latest in a long legacy of atrocities committed by European settlers in North America and the United States Government.

by Susan E. Stutz

Photo by MJ Tangonan

“This is where the wild things are, the place where rivers are clear...it’s our place [and] this is a really bad pipeline that runs through the heart of Ojibwe country in the middle of a time when the planet is on fire.” — W. LaDuke, Ojibwe Leader and Indigenous Rights Organizer.

“We the people” has never meant all the people. In much the same way that man has come to be the word that erroneously describes the entire human race, “we the people” has placed us all, willingly or not, under one nation, one God as though we do not have an independent thought among us. In so doing, it leaves out those who won’t melt into the pot. The first people to feel the bludgeon of this Christian, male-centered brand of American exceptionalism were members of the First Nations.

For upwards of 20,000 years, the ancestors and current members of the First Nations have called this continent home. However, instead of allowing them to live unmolested, those who came from foreign shores did what their forebears had done for millennia—they took what they wanted with no thought, other than one of domination, for the people and land that they were raping, pillaging, and plundering.

Relations between the United States and her First Nation people have been long, and their history has been troubled since the beginning. It is a history replete with hundreds of broken, ignored, or withdrawn treaties between various Tribes and the U.S. government, as European settlers and colonists looked to expand their territory, taking lands and resources to which they were not entitled.

"The people who are citizens of the U.S., these are your treaties. They aren't just the Indians' treaties [...] No one gave us anything. No one was dragging any land behind them when they came here. This was our land." — Jaike Spotted Wolf

Following the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, the United States continued entering into treaties with the various Tribes penning some 350+ treaties between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. These treaties handed millions of acres of tribal land over to the U.S., with various rights reserved to the Tribes. Many treaties included protection for Indians from inter-tribal attacks upon their lands, including legal assistance, recognition of Tribes as sovereign nations, health care, education, money, and religious freedom. The treaties also provided confirmation and protection of certain rights to self-government, fishing, and hunting, as well as jurisdiction over their lands. Additionally, many of those treaties were meant to outline the boundaries of tribal territories and provide compensation for taken lands. Forty-five of them went unratified by the Senate, never becoming law.

One of the most significant aspects of the treaties entered into with the various Tribes is the Tribes continued right to use the lands sold or ceded to the U.S. government. Tribal life revolves around hunting and fishing and the domestic and agricultural use of the lands they call home. This meant that the tribal members would continue to live, work, and play on the lands now owned by the U.S. Additionally, many Tribes retained ownership and usage rights to various natural resources that existed on their reservations.

By the mid-1800s, the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikaras (a/k/a Sahnish) Tribes lived on approximately 12.5 million acres on the Great Plains between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. In addition to their villages becoming an important trading center, the Missouri River itself was a vital resource for the tribal members, yielding food in a few different ways. In addition to fishing in these waters, the river served as a means of obtaining meat for the tribal families. Many grazing animals crossed it every year at the same point and became a regular meat supply for their community. Additionally, when the river rose each year, the Tribes could collect the carcasses of drowned animals. The flowing river also provided driftwood and other materials they could use for housing and different community needs.

An excellent example of the continued controversy surrounding those rights are the mineral rights under the Missouri River in Fort Berthold in North Dakota, and the Three Affiliated Tribes continued ownership of those rights. Following a Department of the Interior review in 2017, the tribal ownership of those mineral rights was confirmed. However, another review in 2020 overturned that opinion, stating that the rights were vested with the State of North Dakota: “The mere fact that the bed of a navigable water lies within the boundaries described in the treaty does not make the riverbed part of the conveyed land.”

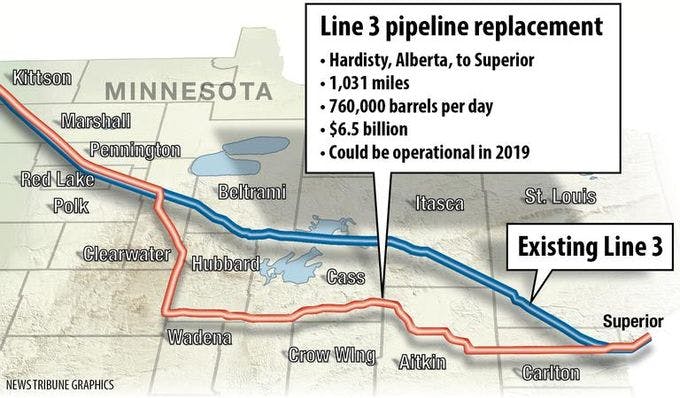

Line 3 and its replacement. Source: Duluth News Tribune

Enbridge’s original pipeline, built in the late 1960s, traveled 1,097 miles from Alberta, Canada to Superior, Wisconsin, crossing over the Leech Lake and Fond du Lac reservations in northern Minnesota. The line was 30” in diameter with a flow rate of 330,000 gallons per day. In July of 2010, the pipeline ruptured near Marshall, Michigan, dumping upwards of 1,000,000 gallons of tar sands oil into Talmadge Creek, which flowed into the Kalamazoo River. At the same time, heavy rains caused the river to overflow, and the oil-laden water traveled 35-40 miles downstream.

The 2010 spill is the second large one that occurred on this same line. In 1991, the line breached, spilling 1.7 million gallons of crude oil. More than 30 years later, it is still the largest inland oil spill in U.S. history. Had it not been for the layer of ice over the river, the outcome, while catastrophic in and of itself, would have been even more so. By Enbridge’s own accounting, there have been 15 large spills from their lines since 1991. Adding insult to injury, there is no plan currently in place to deal with the abandoned Line 3 other than Enbridge will keep an eye on it. This deteriorated pipe, which caused two overwhelmingly catastrophic spills, will sit underground without anyone addressing the potential soil and water contamination.

A crude oil spill is damaging enough. A tar sands oil spill is significantly more dangerous. Tar sands oil, also known as diluted bitumen, does not behave as regular oil does. While it initially sits on the water’s surface, the bitumen changes at an elemental level once it interacts with the environment. Its heavier elements sink to the bottom, causing even more devastation for life in and around the water. This change occurred throughout the first couple of weeks following the 2010 spill. The sunken bitumen also attaches itself to plant life in and around the river. It is almost impossible to remove, and because of the difficulty in removing the sunken bitumen, the clean-up efforts took more than four years with a price tag in the billions. And, even if the tar sands oil traverses the pipeline without incident, the damage caused by the products produced with the oil continues. Sands oil-derived gasoline products produce roughly 15% more carbon emissions than conventional oil. The new pipeline alone is expected to emit more greenhouse gases “than [the] total annual emissions across every sector combined by a factor of 1.25,” in Minnesota.

According to Enbridge and the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, the replacement project “would generally follow the existing Minnesota Pipe Line Company’s right-of-way to Hubbard, Minnesota.” If by “generally,” they mean that it travels south and east, then yes, it generally follows the same path. However, it does not take a genius to recognize that the replacement project is not just replacing a line that no longer functions as it should. In reality, the new pipeline is bigger (36” in diameter) and has a significantly larger capacity than the old line (770,000 gallons per day). Furthermore, the replacement line includes an additional 48 miles of pipe that did not exist before.

Where We Go From Here

“I’m dealing with it by pushing ahead [...] I have no choice but to fight because I’m Indigenous and I want my nieces and nephews and my brothers and sisters to thrive.” — Jaike Spotted Wolf

Construction on Line 3 finished in late September, and the line became operational in October. But, that does not stop the warriors whose genealogy traces back for tens of thousands of years. While the new line was under construction, protestors took up residence at Camp Migizi on the Fond du Lac reservation in North Dakota. They are continuing to fight against Line 3 while, at the same time, looking at other Enbridge pipelines.

Please tune in to Resistbot Live on Sunday, November 21, 2021, as we listen and learn more about Line 3 and its impact on indigenous lands and people.

Support the ’bot!

Upgrade to premium for AI-writing, daily front pages, a custom keyword, and tons of features for members only. Or buy one-time coins to upgrade your deliveries to fax or postal mail, or to promote campaigns you care about!

Upgrade to PremiumBuy Coins